In fiction, when you don’t explicitly tell the reader what’s going on, and instead make them work a little to figure it out, you’ve engaged the reader. The reader then can’t be detached - they’re curious to know what the mystery is, they want to solve the puzzle. This is human nature, and fiction writers can use this to their advantage in constructing a more satisfying story.

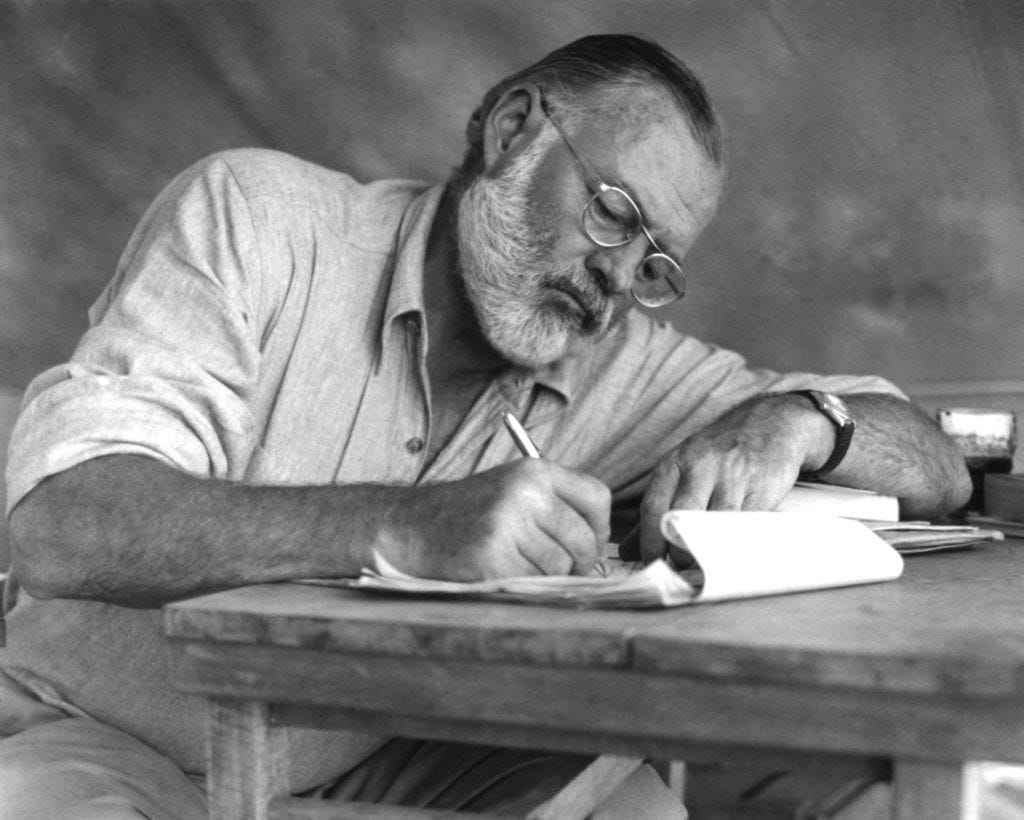

The most famous example in modern literature is Hemingway’s Hills “Like White Elephants.” A couple is waiting in a train station in Spain, going to Madrid. The dialogue of the story, which makes up the bulk of it, is the couple talking about whether or not the woman, Jig, called a girl in the story, should have an abortion. But they never say that word. They talk about an operation, which the man says is easy. They address the subject abstractly, without any talk of details and ramifications, except the man saying he loves her, and the girl saying she doesn’t care about herself, and will do it if just things can stay as they were. Then the story ends, without any real emotional resolution.

What the story does by using this method is bring the reader up close to the intimacy of the dialogue, forcing the reader to read more slowly, ‘listen’ to them and what is and isn’t being said. What isn’t being said says more, in this story, than what they could say if they articulated it.

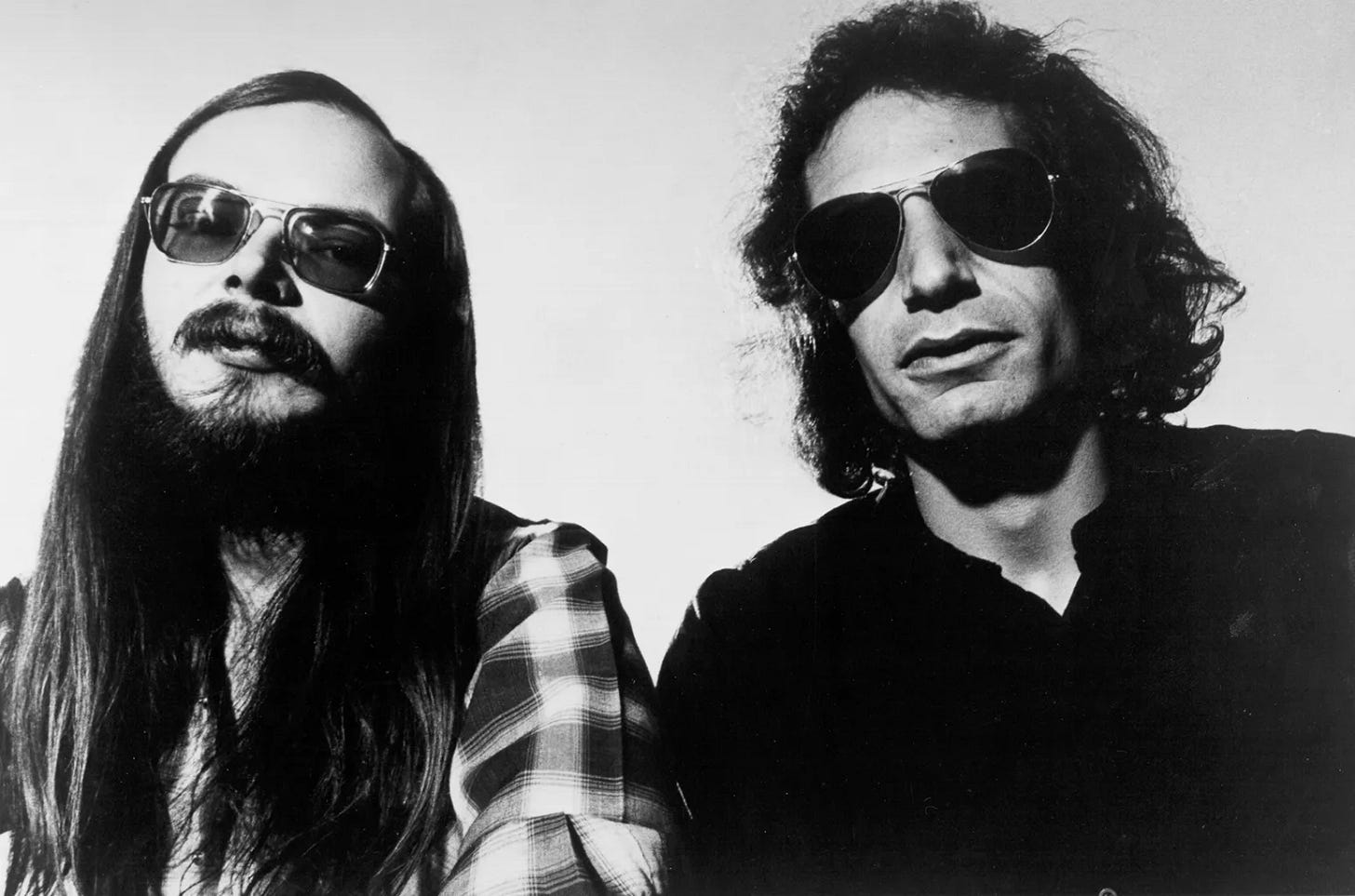

Another example I’d like to use is a very different animal, but one with similar traits. It’s the song, “Pearl of the Quarter,” by Steely Dan.

Here, in a succinct four verses and a chorus, we get the whole story of the relationship, in a setting as satisfying as a complete short story.

On the water down in New Orleans My baby's the pearl of the quarter She's a charmer like you never seen Singing "voulez-voulez-voulez-vous"

The quarter is the French Quarter, a place known for its history and prostitution. Voulez vous means “Do you want to?” or you could translate it as “How about it?” This tells you that his ‘baby’ is a sex worker, (a phrase I’m required to use, in lieu of something more colloquial) who the narrator has fallen for. To the narrator, ‘she’s the pearl of the quarter,’ which means, of course, she’s a jewel, but it’s also a nice descriptive touch, since oystering and fresh oysters are a huge staple in New Orleans cuisine. She’s the pearl that comes out of that area.

Where the sailor spends his hard-earned pay Red beans and rice for a quarter You can see her almost any day Singing "voulez-voulez-voulez-vous"

Louise is may be a pearl to the narrator, but he knows in reality, she’s a cheap date in the low rent area, ‘red beans and rice for a quarter.’

Still, nowhere have the writers, Becker and Fagan, said any of this. They’ve inferred, implied, but not stated. Again, this brings the listener closer to the story. The listener wants to solve the puzzle.

And if you hear from my Louise Won't you tell her I say hello? Please make it clear When her day is done She got a place to go

Here's the real crux of the relationship. The narrator has no illusions about any of it. He knows who she is, knows her real name, Louise, which you can be sure isn’t her working name. He views her tenderly without judging and offers a simple, but profound harbor for her to come to. New Orleans is a harbor town, but in her transient life, he knows she doesn’t have a real home there, and on any night when she might need it, offers his.

I walked alone down the miracle mile I met my baby by the shrine of the martyr She stole my heart with her Cajun smile Singing "voulez-voulez-voulez-vous"

Here, Becker and Fagan reward the listener who wants to dig in with a little research. Tulane Avenue, a long road going out of New Orleans, has traditionally been known as the ‘miracle mile.’ To find “the shrine of the martyr,” just stroll a few blocks east to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church & International Shrine of St. Jude, who, tradition has it, was martyred. One would have to figure that she brought him there and therefore she was religious. What is St. Jude the patron saint of? Impossible cases. This kind of perfect detail, hidden in plain sight, is something Becker and Fagan are famous for, and set throughout their songs like little gems, puzzles waiting for the solving. There are hundreds.

The narrator has had his heart stolen, but has no delusions about their relationship. There is for him only the times when he can see her, paying for her, and then she goes.

She loved the million dollar words I'd say She loved the candy and the flowers that I bought her

Again, Becker and Fagan don’t spell out the class or social difference between the narrator, who is obviously what one might call slumming, but that word denigrates what he’s come to feel for her. Instead, the whole balance and dynamic is in the sentence, “she loved the million dollar words I’d say…” This indicates that she doesn’t understand some of his words, but recognizes them as intelligent and comments on them. This presents a whole picture of playfulness between them, where one can imagine their interactions, but the details are left out for the listener to picture.

Then, in contrast to this special shared thing, she also loves the ordinary gifts of candy and flowers he’s buying for her, accepting them an extra, a thoughtful addition to their paid arrangement. Again, the writers say nothing of this, but it’s implied. When she says she loves him on leaving, it’s especially bittersweet, because he knows she says the same thing to men all day. And she's off to her next client.

In paying attention to the writing, another thing is happening in this verse. The word ‘love’ is used three times, which is a writing no-no. So, perfectionists such as they are, why did Becker and Fagan do that? Because, each time the word love is used here, its power is diminishing. It goes from actual, to routine, to a wave of a goodbye, giving a complete picture of how the narrator sees her love for him, and the hopelessness of his for her.

She said she loved me and was on her way Singing "voulez-voulez-voulez-vous

The longing told of in the chorus now is deeper, more heartrending to the listener, now that we know what the relationship truly is. There's a boundary shattering compassion in the narrator's plea, which isn’t that he wants to say hello, like in the first chorus, but "Won't you tell her that I love her so?" His heart is open and showing his true feelings and again, he’s offering his place to come to, for refuge. Each time he calls her “my Louise,” indicating he’s the only one, of all the men she sees, who truly loves her.

And if you hear from my Louise Won't you tell her I love her so? Please make it clear When her day is done She got a place to go

Becker and Fagan, without once saying it, have taken us through a tender, complicated relationship between a sex worker and a man she’s serviced, the love within that relationship, a clear, unsentimental picture of how it is, and with so much more contained in the song than is actually ever said.